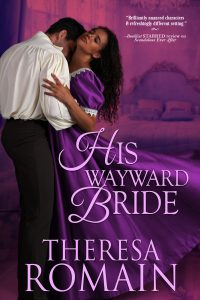

Romance of the Turf book 3

Romance of the Turf book 3

Original publication date: November 5, 2019

Reissue date: February 2022

ASIN: B07XSCPMSC

ISBN: 979-8415196326

Reviews • About the Book • Excerpt

Ebook: amazon • apple • barnes & noble • kobo

Print: amazon

Audio: amazon • apple • audible • google play

Everyone has secrets…

Though their horse-racing family is as troubled as it is talented, all of the Chandler siblings have found love…except eldest brother Jonah. Married four years ago and abandoned after his wedding night, single-minded Jonah now spends his days training Thoroughbreds—while his lost bride is a family mystery no one dares discuss.

And that’s just the way Jonah and his wife, Irene, want it.

The biracial daughter of a seamstress and a con artist, Irene has built a secret career as a spy and pickpocket who helps troubled women. By day she works as a teacher at Mrs. Brodie’s Academy for Exceptional Young Ladies; in spare moments she takes on missions that carry her everywhere from London’s elite heart to its most dangerous corners.

Jonah agreed to this arrangement for four years, until Irene’s family fortunes were made. After surviving on passionate secret meetings and stolen days together, now it’s time to begin the marriage so long delayed. But as these two independent souls begin to build a life together, family obligations and old scandals threaten to tear them apart…

Story elements: Marriage in trouble, spies, workplace romance, care for animals, hidden identity

Content Notes

Depictions of hoarding behavior

References to spousal infidelity (not by hero or heroine)

“[An] enthralling and emotional conclusion to a brilliant series…The characters are so well crafted that I embraced them as real people.”

—Fresh Fiction“An engrossing read that I couldn’t put down until I had finished it.”

—Roses Are Blue

About the Book

- Victor’s scheme to start a boy’s band is, of course, inspired by the plot of The Music Man. He doesn’t get as far with his plan as Harold Hill does, though.

- The illustration of a black woman in the embrace of Prince William Henry is quite real. It was drawn by James Gillray in 1788, and a surviving example belongs to the National Portrait Gallery in London.

- Prince William Henry, the Duke of Clarence and St. Andrews—later King William IV—began a long-standing affair with Dorothea Jordan in 1791. (Irene was born in early 1792.) After he became king in 1831, he bestowed courtesy titles on all of his illegitimate children with Mrs. Jordan. In fiction, we can assume he’d do the same for other children as well. Intriguing, isn’t it?

- Little Miss R named Helena’s foal. So if you think Muffin is a weird name for a horse…well, it is, but it’s no weirder than the horse names I came up with myself.

- The art tutor Aunt Mellie’s children hire at the book’s end isn’t named, but it’s Henry Middlebrook. As a friend of Jonah and Irene’s brother-in-law Bart (Hannah’s husband), he has a family connection. We can assume Henry has been happily building up his teaching practice in the few years since the end of It Takes Two to Tangle.

- For the visual inspiration behind characters, objects, and settings in His Wayward Bride, check out the book’s Pinterest board.

Excerpt

Chapter 1

July 1819

Irene knew these London streets as well as the beat of her heart. With the pawnbroker’s money in her pocket, she dashed and elbowed through crowds. I have enough time, she repeated with each ragged breath. If I hurry, there’s enough time.

Time enough to reach Petticoat Lane. To find the familiar gap in the row of shops and stalls, the narrow entrance to the by-way on which her mother lived. Time enough to pay the landlord. Time enough to avert disaster—again. The church bells had not yet tolled noon. She could still meet Mr. Harris before the eviction.

Why did there always have to be such a rush and surprise, a last-minute scramble?

She knew the answer all too well. Her father had sworn—had sworn—to her mother that he’d pay back the rent money. But the lure of a wager or wench was always too strong for him. This morning, when Irene’s young brother, Laurie, called upon her in a panic at the girls’ academy where she taught, she’d realized that Victor Baird had failed his family once again.

Thank the Lord it was Saturday and Irene had no lessons to teach. No covert missions either. Irene owned the day—and she’d now seize it by protecting her mother and brother from eviction. No thanks to you, Father.

For a largely absent father, Victor Baird had always determined a great deal about Irene’s life. From the American pronunciation of her name—Eye-reen, without the long dancing vowel the English pinned to the name’s end—to the fate of her wedding ring, now nestled in a pawnbroker’s jewelry case.

The state of her marriage…she didn’t know whom to blame for that.

Never mind that. Run. Dodge. Duck. Onward. Would this woman with the plumed hat never decide whether to enter the milliner’s shop? She and her hat took up half the pavement, all mass and indecision.

Aha, a gap in the crowd! Irene tried to slip around the woman, but a stout blow caught her heavily in the ribs, leaving her gasping. In her hurry, she hadn’t noticed the handle of a rag seller’s cart protruding over the pavement. Reeling, she missed a step and lurched into the swift-moving traffic of the street.

Horses, riders, whinnies, shouts. A hint of burnt sugar from a pastry shop. Dust and droppings. The flick of a parasol edged in lace. Shoving pedestrians, the curse of a jarvey who took up rein abruptly. These passed in a whirl, then she stumbled back onto the relative safety of the pavement. Throwing a palm out flat for support, she recovered her balance before the plate-glass window of a shop.

An elderly white man in a tall beaver hat paused, planting his cane beside her. “My dear young la—” He peered over gold-rimmed spectacles, frowning. “Hmph. Are you unwell?”

Young. Ha. Only the aged would call a woman of twenty-seven young. But the man’s broken greeting made Irene’s smile drop as quickly as it had arisen. He’d noticed her light brown complexion and pulled back his polite words. Yet London was home to thousands of people with African heritage, people of every age and status and occupation.

Pulling a breath deep within her aching ribs, Irene straightened her bonnet and shook out her sensible dark blue gown. “I’m quite well, sir. Thank you.” Her tone was frost.

Once the man walked onward, Irene slipped her gloved hands into her pockets. A trained pickpocket knew how vulnerable one was to theft. But all was well, the money as hidden as her newly bare ring finger.

Church bells had chimed the half hour long before. They would peal for noon at any moment. Irene hurried on, plunging back into the whirlpooling crowd.

Then she heard it—a high-pitched whine of animal pain floating above the ordinary street noises.

She halted. Someone bumped into her, then sidled on with a grumble to which she paid no heed. That pained sound came again. A yelp? A hurt dog somewhere near at hand?

Her feet and conscience waged a tense, silent battle. She had to rush on. She had rent to pay. But she couldn’t allow an animal to be hurt.

Conscience won, and she turned her feet toward the sound. It had come from a narrow alley threading off to her right.

A trio of boys drew together, backs to Irene. One lifted a clenched hand. A rock! He was going to throw a rock! The animal whine came again, high and scared.

With determined strides, Irene covered the distance between them. “Boys! Stop!”

Two of the three whipped around, eyes wide. One had light brown skin like Irene; the other was as pale as her father. Their youthful expressions were identically guilty. Exchanging glances, they broke away and hared down the alley.

The remaining boy, red-haired and set-jawed, seemed not to notice. The rock was still in his hand, poised to throw at the cowering dog.

With a second look, Irene recognized him. “Charlie Catton!”

The son of one of her mother’s fellow seamstresses, he startled at the sound of his name. Like Irene’s mother, Susanna, Charlie’s widowed mother eked out a living of meager respectability by stitching away her days above a tonnish dressmaker’s shop.

“Charlie,” Irene chided. “You aren’t going to throw that rock, are you?”

“She stole my food!”

“And hurting her will bring it back, will it?”

The dog cringed, hiding her long-nosed face under filthy front paws. Reluctantly, Charlie dropped the stone to the street and kicked it away.

“But she did steal my food,” he muttered. “I was carryin’ a meat pie home to Mum, and this dog snapped it out of my hand. She gobbled it in one bite and followed me like she wanted more. I tried to chase her away, but she wouldn’t go.”

Hunger padded the streets of London, always. Irene couldn’t fault either dog or boy for their desperation. “And what about the other boys?”

“I dunno them. They said she steals from them too. They were the ones started throwin’ rocks.” Charlie looked away. “I don’t think I would’ve thrown the rock.”

Irene sighed. She had nothing to feed the dog or the boy. And the first bell of noon tolled from a nearby church.

She gritted her teeth in frustration, but there was only one right thing to do: reach into her pocket. “Charlie, take these coins and get more meat pies. One each for you and your mum.”

The bell tolled again, slow and sonorous.

“I’ve got to go. My best to your mother, all right?” She took a half step, then halted. She couldn’t leave the dog here, in case the other boys came back to torment her.

“Come here, girl.” Irene scooped the animal into her arms. The dog was just a puppy, but already large, and her fur was dirty and matted. “I have a call to pay, and you get to come with me. I’ll carry you, though you’re no feather.”

The dog studied Irene with mild brown eyes, then settled into an awkward bundle of limbs. I trust you, the eyes communicated, and with that, Irene rushed back the way she’d come.

Back into the crowds, not far to go. People squeezed along the pavement in both directions. Mud from a recent rain splashed up, wetting Irene’s hem. How many times had the bell tolled? The distance seemed endless, her every step too short.

One street more, and there was the familiar turn. Where it intersected with the main thoroughfare, the buildings were square and confident. As the street wandered farther back, the buildings slumped with fatigue. In one such lodging house, Irene’s mother and thirteen-year-old brother made their home.

But…what was happening? Irene stopped and stared, openmouthed, at the blizzard of belongings snowing from the top story of Harris’s lodging house. In the street below, a knot of people had gathered, curious.

“It only just struck noon,” she whispered. “He promised he wouldn’t toss them out before noon.”

In her arms, the dog whimpered as if echoing her distress.

Recalling herself, Irene snapped out of her startle. She crouched, releasing the dog to the cobbled street. “Stay,” she said. “I’ll be back for you when I can.”

Then, marshaling the composure that served her so well before a classroom, she brushed at her dog-muddied gown and marched toward the gaping throng. Papers flapped down like gulls from the open windows above. Snips of fabric rained like colored fire. The onlookers didn’t bother snatching at these oddments, too small or too soiled to be of any use. They only looked up, agog, at the unending fall of worthless scraps.

Irene shut her eyes for a second. So. Here was the evidence of how bad her mother’s habit had got. Every time Irene visited, it was worse, no matter how much she stealthily carried off to discard. The last time she’d called here, a fortnight before, there had been no place for her to sit amongst the piles of rescued items, as Susanna called them.

Irene shouldered into the ring of people watching. “This isn’t Covent Garden,” she snapped. “It’s a woman’s life, not your entertainment.”

Wrenching open the front door of the lodging house, she wrinkled her nose against the ever-present smell of boiled cabbage. Hardly had she stepped into the cramped foyer before she bumped into the wizened landlord.

“Mr. Harris! Sir!” Irene fumbled for coins. “Call off your helpers. I have my mother’s rent in full.”

Five shillings a week Susanna paid, a steep rent for her plain rooms. Some beetle-headed landlords refused to rent to black families at all, and those who did accept them as tenants charged them a higher rate. At least Harris’s lodging house was both safe and near Susanna’s workplace. With her bad ankle, a short walk was vital.

“Mrs. Chalmers.” Harris greeted Irene with the false name she’d once given him. “You could pay me twenty pounds, and I’d still toss her out. The ceilings are sagging under the weight of her rubbish, and the other tenants are complaining.”

Gray-bearded and bald, Harris was a stooped man with rheumy blue eyes. For the year and a half Irene had known him, he’d spoken with a wheeze, coughing into a blood-specked handkerchief. His physician had expected him to be in the grave long ago, he had once told Irene, but he was too stubborn to do as expected.

Irene respected stubbornness. It had carried her far. She used it now, wheedling, “It’s just paper and cloth. How bad could it be? My mother is employed steadily, and she is a respectable tenant.”

“I warned her a week ago, she’d be out unless she cleared her rooms of rubbish by this morning. She didn’t discard a single piece.” Coughing into his handkerchief, he gestured with his free hand toward the doorway. “So I’m having the rooms cleared for her. The quick way.”

Damnation.

Though she hadn’t known of this demand, Irene could not fault the elderly man. She could hardly stand to be in her own mother’s company, since such company was wed to innumerable, pressing belongings. Even now, a good daughter would be climbing the steps, taking Susanna’s hands, comforting Laurie. Rescuing what possessions they could use. Planning where they could go next.

Instead, Irene turned away from the stairs. Outside the doorway, her mother’s hoard fell like a soft rain on this sullen summer day.

She had failed.

All the skills she’d developed over the past six years, and none of them did her any good now. The maps she’d memorized, the pockets she’d picked, the letters she’d stolen, the reputations she’d saved. All to help women like her mother, who had placed their trust in the wrong men—yet her mother was the one woman she couldn’t help.

Susanna descended the stairs, the stutter-stomp of her listing gait unmistakable. When she rounded the turn in the staircase, she spoke up, her tone sweet but unyielding. “Mr. Harris, this will not do. Your friends are laying hands on my personal belongings.”

Harris hid behind his handkerchief. “They’re not friends. They’re the sons of the butcher at the end of the lane.”

“Their identities are the least of my concerns. You must have them stop.” Susanna Baird reached the foyer floor and stood with eyebrows lifted. Waiting for action with a quiet certainty.

Irene’s mother was lovely and petite, with dark skin burnished warm by the yellow stripe of her gown. Perhaps Susanna’s confidence came from her ability, for she was a masterful seamstress who could fashion elegance from little more than sackcloth and wishes.

“Where’s Laurie?” Irene craned her neck to see whether her brother had followed their mother downstairs.

Susanna didn’t shift her gaze from the landlord. “Upstairs. In the rooms which ought still to be ours. Trying to reason with the people Mr. Harris sent to throw a paying tenant’s worldly possessions out into the street.”

“About that,” Irene began delicately. “The paying-tenant bit, I mean. Father didn’t pay. Laurie came to tell me this morning. But I can cover the week’s rent for you.”

“You can’t,” Harris insisted. “They have to go.” He looked at Irene’s mother, his drooping eyes doleful over the handkerchief pressed to his mouth. “You know you have to go, Mrs. Baird.”

Susanna regarded him calmly. “Do you want me to beg you? Here, I will fall to the floor before you. Step on me, but do not leave my son without a roof over his head.” She started to sink to her knees.

Harris looked discomfited. “Mrs. Baird, please.”

“Mama, your bad ankle,” Irene reminded her. “You shouldn’t strain it.”

“Fine, I won’t kneel. I’ll sit.” Susanna sat on the bottom stair, leaning against the side of the stairwell. “And I’ll get up when you give us another week.”

“You’re blocking the stairs,” Harris pointed out.

Susanna eased her stiff ankle into a more comfortable position. “Then I suppose no one can use the stairs anymore. Unless you want to give us another week, in which case I’ll get up.”

“That’s—” Irene snapped her mouth shut. Brilliant, she did not say, since Harris was listening and clearly annoyed.

Light footsteps sounded on the stairs just then. Laurie appeared, thirteen years old and wiry, clambering over his mother to stand beside Irene in the foyer. “What’s going on?”

“Nothing you need to worry about.” Irene pulled him into a quick embrace. He was the spit of their mother but already taller than her. “Everything’s all right.”

Laurie struggled free. “Whenever you say everything’s all right, it means it’s not. Because if everything’s fine, then we know it, and we don’t have to say so.”

“Of course everything is fine,” Irene hedged. “You see Mr. Harris and Mama right here, discussing what’s to be done next.”

“So good of him,” Susanna said, “not to leave my boy without a roof over his head.”

The old man glared at both women.

Let him glare, if it softened his heart toward Laurie. Laurie hadn’t cluttered and crammed the rented rooms. Laurie hadn’t broken promises to clean them up. Laurie hadn’t borrowed the rent money, as their father had, or speculated with the savings for his school fees.

And Laurie hadn’t burned time pawning a ring. Laurie hadn’t stopped to help a dog that, judging from the joyful yelps outside, was so friendly she had no need of a rescuer.

Distress tensed Irene’s shoulders. “How much do you need, Mr. Harris, for one more week’s lodging?”

Before he could protest, she held up a palm. “Only one more week, and I will pay in advance. But you must realize that my mother needs time to find another place to live. And her rooms are being cleared, so the hoard won’t be a problem anymore.”

Promise now, sort it out later—though God only knew how. Irene would be teaching during the week, with no more salary until the next quarter day. And that was already promised to the banker in Barrow-on-Wye.

No matter; she’d arrange something. She’d tutor students or take an extra mission for the headmistress. Given time, she would solve the problem. She just needed time.

Harris was still hesitating. Irene took a coin from her pocket and turned it in her hand, letting the sun filtering into the dim foyer wink and play off the silver.

“One week.” She palmed that coin, took out another one. The moment was taut; Irene let it stretch tighter.

And at last: “One week,” Harris agreed, one crabbed hand grabbing the coins as his other pressed the handkerchief against a new round of coughing. “But they must go at the end of it.”

“Fine.” Irene wouldn’t show her relief, but she could have capered with it.

“Fine,” said Susanna. True to her word, she popped up from her seat on the stair, then strode through the front door.

“And your mother isn’t to bring anything back into the rooms that I’ve had thrown out,” Harris added.

Irene’s urge to caper melted away. “Ah.” But what could she say? “Of course she won’t.”

Unfortunately, Susanna chose this moment to stalk back into the lodging house, arms full of papers and cloth scraps and…was that a fishhook? Irene shut her eyes, praying for a reprieve.

The raspy bark of a dog provided it. Then the scrabbling of claws and the thump thump of a busy tail.

Irene opened her eyes to the sight of her new companion, the puppyish creature, winding around Harris’s legs. Susanna peered over her armful of so-called treasures, curious.

“What’s this?” Harris waved a hand at the animal orbiting him.

“A dog,” Irene replied.

Amusement flickered on the landlord’s features. “From where? Whose is it?”

“No one’s, probably. I brought her with me. Some boys were throwing rocks at her.”

Laurie crouched to the dog’s level, letting the cold nose touch his own, and reached out to pet the shaggy fur.

“So you rescued her.” Susanna dipped her chin toward the items she held. “Because some things deserve better than to be tossed away.”

Irene tried again. “Mama. If you could assure Mr. Harris that—”

“No. I must reconsider,” Harris cut her off. “Mrs. Chalmers, another week will only allow your mother to—”

“Sorry to interrupt.” A masculine voice broke into the increasing clamor in the foyer. “But I believe I’ve located something of mine.”

That voice. That voice. It raised prickles on the back of Irene’s neck. It was a voice for sweet bottled days and secrets, and it didn’t belong here.

Slowly, she turned on her heel. And there he was, broad and sturdy as oak. Strong-featured and suntanned, with sandy-brown hair and intense hazel eyes. Calm and steady as if he’d always been there.

Irene noticed all this in an instant, and in another, her breath was gone as if she’d never stopped running. “You’re early,” she managed to say. “I didn’t expect you yet.”

Susanna lowered her armful of rescued scraps. “Who is this? Someone else come to take away my belongings?”

“In a sense.” Irene couldn’t look away from the hazel gaze. “Mama, this is Jonah Chandler. My husband.”

* * *

Ebook: amazon • apple • barnes & noble • kobo

Print: amazon

Audio: amazon • apple • audible • google play